Flashdance

| Flashdance | |

|---|---|

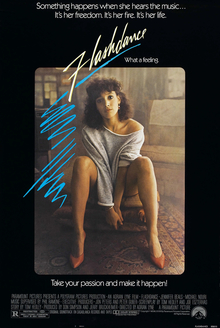

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Adrian Lyne |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | Tom Hedley |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Donald Peterman |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Giorgio Moroder |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7 million |

| Box office | $201.5 million[2] |

Flashdance is a 1983 American romantic drama dance film directed by Adrian Lyne and starring Jennifer Beals as a passionate young dancer, Alex Owens, who aspires to become a professional ballerina, alongside Michael Nouri, who plays her boyfriend and the owner of the steel mill where she works by day in Pittsburgh. It was the first collaboration of producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, and the presentation of some sequences in the style of music videos was an influence on other 1980s films including Footloose, Purple Rain, and Top Gun, Simpson and Bruckheimer's most famous production. It was also one of Lyne's first major film releases, building on television commercials.[3] Alex's elaborate dance sequences were shot using body doubles (Beals's main double was the uncredited French actress Marine Jahan, while a breakdance move was doubled by the male dancer Crazy Legs).[4]

The film opened to negative reviews by professional critics, including Roger Ebert, who panned it as "great sound and flashdance, signifying nothing" (and eventually placed it on his "most hated" list).[5] It was a surprise box-office success, becoming the third-highest-grossing film of 1983 in the United States.[6] Its worldwide box-office gross exceeded $200 million.[2] The soundtrack, compiled by Giorgio Moroder, spawned several hit songs, including "Maniac" (performed by Michael Sembello), and the Academy Award–winning "Flashdance... What a Feeling", which was written for the film by Moroder, with lyrics by Keith Forsey and the singer Irene Cara. Flashdance is also often remembered for its film poster featuring Beals sporting a sweatshirt with a large neck hole (according to the actress, her look in the scene came about by accident after she simply cut a large hole at the top of one that had shrunk in the wash).

Plot

[edit]

Alex Owens is an eighteen-year-old welder at a steel mill in Pittsburgh, who lives with her dog, Grunt, in a converted warehouse. She aspires to become a professional dancer, but has no formal dance training and works as a nightly cabaret performer at Mawby's, a neighborhood bar and grill.

Lacking family, Alex bonds with her coworkers at Mawby's, some of whom also aspire to greater artistic achievements. Jeanie, a waitress, is training to be a figure skater, while her boyfriend, short-order cook Richie, hopes to become a stand-up comic.

One night, Alex catches the eye of customer Nick Hurley, the owner of the steel mill where she works. After learning that she is one of his employees, he pursues her on the job, though Alex turns down his advances. Alex is also approached by Johnny C., who wants her to dance at his nearby strip club, Zanzibar.

After seeking counsel from her mentor, retired ballerina Hanna Long, Alex attempts to apply to the Pittsburgh Conservatory of Dance and Repertory. She becomes intimidated by the scope of the application process, which includes listing all prior dance experience and education, so she leaves without applying. Leaving Mawby's one evening, Richie and Alex are assaulted by Johnny C. and his bodyguard, Cecil. Nick intervenes, and after following Alex home, the two begin a relationship.

In a skating competition, Jeanie falls twice during her performance and sits defeated on the ice before being helped away. Discouraged by her failure and the departure of Richie, who has decided to try his luck in Los Angeles, Jeanie begins dating Johnny C. and working as one of his strippers at Zanzibar. After finding out about Jeanie's situation from Jake, the owner of Mawby's, Alex finds her and drags her out of Zanzibar. Jeanie is angry, but she soon realizes her mistake.

After seeing Nick with a woman at the ballet one night, Alex throws a rock through a window of his house, only to discover that it was his ex-wife, whom he was meeting for a charity function. Alex and Nick reconcile, and she gains the courage to apply to the Conservatory. He uses his connections with the arts council to get Alex an audition, as she does not have formal dance training.

Upon discovering this, Alex is furious with Nick because she did not get the opportunity based on her own merit, so she decides not to go to the audition. After the sudden death of Hanna and seeing the results of others' failed dreams, Alex becomes despondent over her future, but following a conversation with another dancer at Mawby's, who encourages her to persevere, Alex has a change of heart and goes through with the audition after all.

At the audition, Alex falters, but begins again and successfully completes a dance number composed of moves that she has studied and practiced, including breakdancing which she has seen on the streets of Pittsburgh. The board responds favorably, and she joyously emerges from the Conservatory to find Nick and Grunt waiting for her with a bouquet of roses.

Cast

[edit]- Jennifer Beals as Alexandra "Alex" Owens

- Michael Nouri as Nick Hurley

- Lilia Skala as Hanna Long

- Sunny Johnson as Jeanie Szabo

- Kyle T. Heffner as Richie Blazek

- Lee Ving as Johnny C.

- Ron Karabatsos as Jake Mawby

- Belinda Bauer as Katie Hurley

- Malcolm Danare as Cecil

- Don Brockett as Pete

- Cynthia Rhodes as Tina Tech

- Durga McBroom as Heels

- Phil Bruns as Frank Szabo

- Micole Mercurio as Rosemary Szabo

- Lucy Lee Flippin as Secretary

- Stacey Pickren as Margo

- Bob Harks as Priest

- Liz Sagal as Sunny

- Marine Jahan (uncredited) as Alexandra Owens in dance sequences

- Jumbo Red as Grunt

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]In April 1980, Thomas Hedley sold the film idea for development to Casablanca, a Los Angeles production company, for $300,000 and 5% of the net, as reported in The Globe and Mail. Hedley based the concept on the lives of exotic dancers he had met while editor of Toronto Life magazine such as Gina Healey and Maureen Marder. Marder and Healey were paid $2,500 each for their life stories.[7][8]

Hedley's script was eventually sold to Peter Guber and Jon Peters for PolyGram Pictures, who took the script with them to Paramount Pictures. However, the latter studio had less confidence in the film and placed it into turnaround for two years. Development of the film resumed when Don Simpson, who believed the film could be successful, resigned from his executive post at Paramount Pictures to co-produce the film with Jerry Bruckheimer in their first collaboration. They got Paramount to greenlight the film by hiring Joe Eszterhas to rewrite Hedley's script.[7]

Adrian Lyne was not the first choice as director of Flashdance. David Cronenberg had turned down an offer to direct as he felt he would have destroyed the film, as had Brian De Palma, who instead chose to direct Scarface (1983). At the time, Lyne's background was primarily in directing television commercials, such as his 1970s UK commercials for Brutus Jeans (which may conceivably be seen as anticipating the visuals and style of Flashdance).[3][9] Lyne agreed to direct because he wanted to establish enough confidence from studios in his directorial skills to get his next film 9½ Weeks (1986) approved.[10] Executives at Paramount were unsure about the film's potential and sold 25% of the rights prior to its release.

Casting

[edit]Three candidates, Jennifer Beals, Demi Moore, and Leslie Wing, were the finalists for the role of Alex Owens. Two different stories exist regarding how Beals was chosen. One states that then-Paramount president Michael Eisner asked women secretaries at the studio to select their favorite after viewing screen tests. The other: the film's scriptwriter Joe Eszterhas claims that Eisner asked "two hundred of the most macho men on the [Paramount] lot, Teamsters and gaffers and grips ... 'I want to know which of these three young women you'd most want to fuck.'"[11][12][13]

The role of Nick Hurley was originally offered to Kiss founding member Gene Simmons,[14] who turned it down because it would conflict with his "demon" image. Kevin Costner, a struggling actor at the time, came very close for the role of Nick Hurley, which went to Michael Nouri.[14]

Crew

[edit]Flashdance was the first success of a number of filmmakers who became successful in the 1980s and beyond. The film was the first collaboration between Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, who went on to produce Beverly Hills Cop (1984) and Top Gun (1986). Eszterhas received his second screen credit for Flashdance, while Lyne went on to direct 9½ Weeks (1986), Fatal Attraction (1987), Indecent Proposal (1993), and Lolita (1997). Lynda Obst, who developed the original story outline, went on to produce Adventures in Babysitting (1987), The Fisher King (1991), and Sleepless in Seattle (1993).

Filming

[edit]The film was shot between October 18, 1982 and December 30, 1982 in Pittsburgh and Los Angeles.

The dimly lit cinematography and montage-style editing are due in part to the fact that most of Jennifer Beals' dancing in the film was performed by a body double.[15] Her main dance double is the French actress Marine Jahan,[16][17][18][19] while the breakdancing that Alex performs in the audition sequence at the end of the film was doubled by the male dancer Crazy Legs.[20] The shot of Alex diving through the air in slow motion during the audition sequence was performed by Sharon Shapiro, who was a professional gymnast.[20] The producers of the film stated they had made no secret of having used a double for Beals, and that Jahan's name did not appear because Paramount Pictures shortened the closing credits.[15] Marine Jahan was told that her involvement was hidden because "they didn't want to break the magic of the film".[21][22]

Flashdance is often remembered for the sweatshirt with a large neck hole that Beals wore on the poster advertising the film. Beals said that the look of the sweatshirt came about by accident when it shrank in the wash and she cut out a large hole at the top so that she could wear it again.[23]

Locations

[edit]Much of the film was shot in locations around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[7] The opening sequence of scenes with Alex riding her bicycle starts in the Fineview neighborhood.[24] The last scene of the sequence shows Alex riding east over the Smithfield Street Bridge, which is a continuity error. Alex's apartment was located in the South Side neighborhood.[24] When Alex goes to visit Hanna, she is seen riding one of the Duquesne Incline cable cars.[25] Hanna's apartment is located at 2100 Sidney Street at the southeast corner of South 21st Street.[25]

The fictional Pittsburgh Conservatory of Dance and Repertory was filmed inside the lobby and in front of Carnegie Music Hall, a part of the Carnegie Museum of Art, located near the campuses of Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh.[24]

The interior of Alex's apartment was filmed in Los Angeles at what was the Feit Electric Building on Los Angeles Street.[25] Additionally, the set for Mawby's was located in downtown Los Angeles.[7] The ice skating rink scene on which Jeanie falls was filmed at Culver Ice Rink in Culver City, California.[26]

Music

[edit]"Flashdance... What a Feeling" was performed by Irene Cara, who also sang the title song for the similar 1980 film Fame. The music for "Flashdance... What a Feeling" was composed by Giorgio Moroder, and the lyrics were written by Cara and Keith Forsey. The song won an Academy Award for Best Original Song, as well as a Golden Globe and numerous other awards. It also reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in May 1983. Despite the song's title, the word 'Flashdance' itself is not heard in the lyrics. The song is used in the opening title sequence of the film, and is the music Alex uses in her dance audition routine at the end of the film.

Another song used in the film, "Maniac", was also nominated for an Academy Award. It was written by Michael Sembello and Dennis Matkosky. A popular urban legend holds that the song was originally written for the 1980 horror film Maniac, and that lyrics about a killer on the loose were rewritten so the song could be used in Flashdance. The legend is discredited in the special features of the film's DVD release, which reveal that the song was written for the film, although only two complete lyrics ("Just a steel town girl on a Saturday night" and "She's a maniac") were available when filming commenced. Like the title song, it reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in September 1983.[27][28]

Other songs in the film include "Lady, Lady, Lady", performed by Joe Esposito, "Gloria" and "Imagination" performed by Laura Branigan, and "I'll Be Here Where the Heart Is", performed by Kim Carnes.

The soundtrack album of Flashdance sold 700,000 copies during its first two weeks on sale and has gone on to sell over six million copies in the U.S. alone. In 1984, the album won the Grammy Award for Best Album of Original Score Written for a Motion Picture or a Television Special.

Release

[edit]Flashdance was released in the United States on April 15, 1983.[7] On April 14, 1983, the night before the general release of the film, a special benefit premiere of Flashdance was shown at the Warner Theater in Pittsburgh. It was the last film at the theater. Several months later it was torn down to make way for The Warner Centre, a retail and office complex. [29]

Home media

[edit]Flashdance has been issued originally on VHS and Laserdisc with a Paramount Pictures DVD release on October 8, 2002 and a Special Collector's Edition DVD in 2010.[30][31] It was first released on Blu-ray Disc on August 13, 2013 by Warner Bros. with seven special features including a 15-minute featurette, "The History of Flashdance", a 9-minute featurette, "The Look of Flashdance", "Flashdance: The Choreography" and a teaser and theatrical trailers.[32] The film was re-released on Blu-ray in the U.S. on May 19, 2020 by Paramount Presents with a new 4K remaster and packaging. It includes a new Filmmakers Focus interview with the director but excludes a few special features from the previous Blu-ray release.[33]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 37% based on 49 reviews, with an average rating of 4.80/10. The site's consensus is: "All style and very little substance, Flashdance boasts eye-catching dance sequences—and benefits from an appealing performance from Jennifer Beals—but its narrative is flat-footed".[34] On Metacritic the film has a score of 39% based on reviews from 11 critics, indicating "generally unfavorable reviews".[35]

Roger Ebert placed it on his list of Most Hated films,[5] and in giving the film 1.5 out of 4 stars in his review, stated: "Jennifer Beals shouldn't feel bad. She is a natural talent, she is fresh and engaging here, and only needs to find an agent with a natural talent for turning down scripts".[36] In his review for the Chicago Sun-Times, Ebert said "If Flashdance had spent just a little more effort getting to know the heroine of its story, and a little less time trying to rip off Saturday Night Fever, it might have been a much better film."[36] Variety compared the film to a series of music videos, "Watching Flashdance is pretty much like looking at MTV for 96 minutes. Virtually plotless, exceedingly thin on characterization and sociologically laughable, pic at least lives up to its title by offering an anthology of extraordinarily flashy dance numbers."[37] Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote: "With a score by Giorgio Moroder, and with ingenious costumes that are utterly au courant, Flashdance contains such dynamic dance scenes that it's a pity there's a story here to bog them down."[38]

In a 1984 essay for the journal Jump Cut, critic Kathryn Kalinak questioned the characterization of Alex: "How could an 18 year-old woman land a skilled labor job as a welder in the unionized steel industry of an economically depressed union town? ... Not only are any other women missing in the factory, so are employees, male or female, under 30."[39]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Cinematography | Donald Peterman | Nominated | [40] |

| Best Film Editing | Bud S. Smith and Walt Mulconery | Nominated | ||

| Best Original Song | "Flashdance... What a Feeling" Music by Giorgio Moroder; Lyrics by Keith Forsey and Irene Cara |

Won | ||

| "Maniac" Music and Lyrics by Michael Sembello and Dennis Matkosky |

Nominated | |||

| American Cinema Editors Awards | Best Edited Feature Film | Bud S. Smith and Walt Mulconery | Nominated | |

| Blue Ribbon Awards | Best Foreign Film | Adrian Lyne | Won | |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Editing | Bud S. Smith and Walt Mulconery | Won | [41] |

| Best Score for a Film | Giorgio Moroder | Nominated | ||

| Best Original Song Written for a Film | "Flashdance... What a Feeling" Music by Giorgio Moroder; Lyrics by Keith Forsey and Irene Cara |

Nominated | ||

| Best Sound | Don Digirolamo, Robert Glass, Robert Knudson, and James E. Webb | Nominated | ||

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Nominated | [42] | |

| Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Jennifer Beals | Nominated | ||

| Best Original Score – Motion Picture | Giorgio Moroder | Won | ||

| Best Original Song – Motion Picture | "Flashdance... What a Feeling" Music by Giorgio Moroder; Lyrics by Keith Forsey and Irene Cara |

Won | ||

| "Maniac" Music and Lyrics by Michael Sembello and Dennis Matkosky |

Nominated | |||

| Golden Raspberry Awards | Worst Screenplay | Screenplay by Tom Hedley and Joe Eszterhas; Story by Tom Hedley |

Nominated | [43] |

| Grammy Awards | Album of the Year | Flashdance: Original Soundtrack from the Motion Picture Various Artists and Giorgio Moroder |

Nominated | [44] |

| Record of the Year | "Flashdance... What a Feeling" – Irene Cara and Giorgio Moroder | Nominated | ||

| "Maniac" – Phil Ramone and Michael Sembello | Nominated | |||

| Song of the Year | "Maniac" – Dennis Matkosky and Michael Sembello | Nominated | ||

| Best Pop Vocal Performance, Male | "Maniac" – Michael Sembello | Nominated | ||

| Best Pop Vocal Performance, Female | "Flashdance... What a Feeling" – Irene Cara | Won | ||

| Best Pop Instrumental Performance | "Love Theme from Flashdance" – Helen St. John | Nominated | ||

| Best Instrumental Composition | "Love Theme from Flashdance" – Giorgio Moroder | Won | ||

| Best Album of Original Score Written for a Motion Picture or a Television Special | Flashdance: Original Soundtrack from the Motion Picture Michael Boddicker, Irene Cara, Kim Carnes, Doug Cotler, Keith Forsey, Richard Gilbert, Jerry Hey, Duane Hitchings, Craig Krampf, Ronald Magness, Dennis Matkosky, Giorgio Moroder, Phil Ramone, Michael Sembello, and Shandi Sinnamon |

Won | ||

| Hochi Film Awards | Best International Picture | Adrian Lyne | Won | |

| Japan Academy Prize | Outstanding Foreign Language Film | Nominated | ||

| NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Actress in a Motion Picture | Jennifer Beals | Won | |

| National Music Publishers' Association | Best Song in a Movie | Irene Cara | Won | |

| People's Choice Awards | Favorite Theme/Song from a Motion Picture | "Flashdance... What a Feeling" | Won | |

| Satellite Awards | Best DVD Extras | Nominated | [45] | |

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Flashdance... What a Feeling" – #55[46]

Legacy

[edit]There were discussions about a sequel, but the film was never made. Beals turned down an offer to appear in a sequel, saying: "I've never been drawn to something by virtue of how rich or famous it will make me. I turned down so much money, and my agents were just losing their minds."[47]

In March 2001, a Broadway musical version was proposed with new songs by Giorgio Moroder, but failed to materialize.[48] In July 2008, a stage musical adaptation Flashdance The Musical premiered at the Theatre Royal in Plymouth, England. The book is co-written by Tom Hedley, who created the story outline for the original film, and the choreography is by Arlene Phillips.[49]

In October 2020, Paramount announced plans to reboot the film as a TV series for Paramount+.[50]

Jennifer Beals' performance started her reputation as a lesbian icon.[51]

Connection to MTV

[edit]Flashdance is not a musical in the traditional sense as none of the characters sing or dance, although the Alex character is portrayed as an amateur dancer, but rather the songs are presented in the style of self-contained music videos. Its success has been attributed in part to the 1981 launch of the cable channel MTV (Music Television) since it was the first feature film to exploit the new popularity of music videos effectively.[52] By excerpting segments of the film and running them as music videos on MTV, the studio benefited from extensive free promotion, establishing the new medium as an important marketing tool for films.[53] In the mid-1980s, it became almost obligatory to release a music video to promote a major motion picture—even if the film was not especially suited for one.[54]

Legal action

[edit]Suit against the filmmakers

[edit]Flashdance was inspired by the real-life story of Maureen Marder, a construction worker/welder by day and dancer by night at Gimlets, a Toronto strip club.[8] Like Alex Owens in the film, she aspired to enroll in a prestigious dance school. Tom Hedley wrote the original story outline for Flashdance, and on December 6, 1982, Marder signed a release document giving Paramount Pictures the right to portray her life story on screen, for which she was given a one-off payment of $2,300. Flashdance is estimated to have grossed more than $200 million worldwide. In June 2006, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco affirmed a lower court's ruling that Marder gave up her rights to the film when she signed the release document in 1982. The panel of three judges stated in its ruling: "Though in hindsight the agreement appears to be unfair to Marder—she only received $2,300 in exchange for a release of all claims relating to a movie that grossed over $150 million—there is simply no evidence that her consent was obtained by fraud, deception, misrepresentation, duress or undue influence." The court also noted that Marder's attorney had been present when she signed the document.[55]

Suit against Jennifer Lopez and filmmakers over music video

[edit]In 2003, following the use of dance routines from the film by Jennifer Lopez in her music video "I'm Glad" (directed by David LaChapelle), Marder sued Lopez, Sony Corporation (the makers of the music video), and Paramount in an attempt to gain a copyright interest in the film. Although Lopez argued that her video for "I'm Glad" was intended as a tribute to Flashdance, Sony settled a copyright infringement lawsuit out of court for the use of dance routines and other story material from the film in the video.[56][57]

See also

[edit]- It's Flashbeagle, Charlie Brown

- List of American films of 1983

- Duquesne Brewery Clock

- Dance, Girl, Dance

References

[edit]- ^ "Flashdance (15)". British Board of Film Classification. April 27, 1983. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ a b "Box Office Information for Flashdance". The Numbers. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Delaney, Sam (August 23, 2007). "The British admen who saved Hollywood". The Guardian. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ DeFrantz, Thomas F (2014). "Hip-Hop in Hollywood: Encounter, Community, Resistance". In Melissa Blanco Borelli (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Dance and the Popular Screen. Oxford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-19-989783-4.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (August 11, 2005). "Roger Ebert's Most Hated list". Rogerebert.suntimes.com. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ "1983 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Flashdance (1983)". American Film Institute. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Roberts, Soraya (August 14, 2014). "The Secret History Of "Flashdance"". BuzzFeed. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

Based on the terms of his deal with Casablanca, Hedley came out $8 million richer. The Zabols, however, received neither credit nor payment nor were their slides ever returned. Meanwhile, Gina Healey and Maureen Marder were paid $2,300 each for signing away their life stories to Paramount and agreeing never to talk about their involvement...And this time, Gina Healey, Maureen Marder, and the Zabols are refusing to keep quiet about its backstory, despite the risk of litigation.

- ^ Croll, Ben (December 1, 2024). "David Cronenberg Doesn't Regret Turning Down 'Flashdance' Producers Jerry Bruckheimer and Don Simpson: 'I Told Them, I Will Destroy Your Movie If I Direct It'". Variety. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ "Nine 1/2 Weeks". AFI Catalog. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ Curtis, Bryan (February 3, 2004). "The Condensed Joe Eszterhas". Slate Magazine.

- ^ Thomas, Mike (January 20, 2011). "Jennifer Beals returns to Chicago with new cop drama". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ Eszterhas, Joe (May 5, 2010). Hollywood Animal. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 170–171. ISBN 9780307530875. Retrieved August 22, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b McKairnes, Jim (April 12, 2018). "What a feeling! Break out the legwarmers, because 'Flashdance' turns 35". USA Today. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "Dancer not getting credit for work in "Flashdance"". Lakeland Ledger. April 22, 1983.

- ^ Fuhrer, Margaret (February 27, 2018). "Our Favorite Movie Dance Doubles of All Time". Dance Spirit. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ "Making Flashdance look flashy". Eye For Film. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ "Hoofers Hidden in the Shadows Dream of the Limelight". People. April 2, 1984. Archived from the original on September 12, 2010.

- ^ Bierly, Mandi (September 28, 2007). "Maniac on the Floor". Entertainment Weekly. No. 956. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007.

- ^ a b "'Flashdance,' 30 Years Later: B-Boy Recalls Girling Up for Final Scene". Yahoo! News. April 15, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ Murphy, Eileen (March 27, 2011). "Revenge of the Body Doubles: 'Black Swan' Snub". ABC News. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ Pollard, Tom (June 1, 2018). "Flashdance (1983)". Popular Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on October 4, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

It seems that she didn't get credit for her work because the studio didn't have to. It was either never required in the contract she signed

- ^ Salem, Rob (February 16, 2011). "Jennifer Beals: From ripped sweats to dress blues". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c "This Week in Pittsburgh History: Flashdance Opens in Theaters". Pittsburgh Magazine. April 12, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Flashdance". movie-locations.com. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ "Flashdance". itsfilmedthere.com. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ "Maniac by Michael Sembello Songfacts". Songfacts.com. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ "Billboard Charts Archive - 1983". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Crowley, Patrick. "Warner Theater". CinemaTreasures.org. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ "Flashdance DVD". Blu-ray.com. October 8, 2002. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Flashdance Special Collector's Edition DVD". Blu-ray.com. October 8, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ "Flashdance Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. August 13, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Flashdance Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. May 19, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Flashdance". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on September 30, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ "Flashdance". Metacritic. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (April 19, 1983). "Flashdance". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ "Flashdance". Variety. January 1, 1983.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (April 15, 1983). "Pittsburgh and Dance". The New York Times.

- ^ Kalinak, Kathryn (February 1984). "Flashdance: The dead end kid". Jump Cut (29): 3–5.

- ^ "The 56th Academy Awards (1984) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1984". British Academy Film Awards. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "Flashdance". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "4th Golden Raspberry Awards". Golden Raspberry Awards. Archived from the original on October 28, 2006.

- ^ "26th Annual GRAMMY Awards". Grammy Awards. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ "International Press Academy website – 2007 12th Annual SATELLITE Awards". International Press Academy. December 16, 2007. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs". American Film Institute. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ "Beals Turned Down Flashdance Sequel". contactmusic.com. August 18, 2003. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011.

- ^ Hofler, Robert (March 22, 2001). "What a feeling: 'Flashdance' fever". Variety. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Atkins, Tom (February 8, 2008). "Flashdance Debuts in Plymouth, Sweeney Shouts". WhatsOnStage. Archived from the original on October 19, 2008.

- ^ Goldberg, Lesley (October 21, 2020). "'Flashdance' TV Reboot in the Works at Paramount+ (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ White, Adam (January 29, 2020). "Jennifer Beals: 'You can never have enough stories about the queer community'". The Independent.

- ^ Calavita, Marco (2007). ""MTV Aesthetics" at the Movies: Interrogating a Film Criticism Fallacy". Journal of Film and Video. 59 (3): 15–31. doi:10.2307/20688566. ISSN 0742-4671. JSTOR 20688566. S2CID 59499664.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (June 4, 1983). "'Invisible Marketing' Helps 'Flashdance' Sell". The New York Times.

- ^ Litwak, Mark (1986). Reel Power: The Struggle for Influence and Success in the New Hollywood. Morrow. p. 245. ISBN 978-1879505193. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Herel, Suzanne (June 13, 2006). "SAN FRANCISCO / Inspiration for 'Flashdance' loses appeal for more money". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Zacharek, Stephanie (May 11, 2003). "TELEVISION/RADIO; Meet Jenny From the Steel Mill". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015.

- ^ Susman, Gary (April 14, 2013). "Jennifer Lopez's "I'm Glad" video". Time. Time Inc. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Flashdance at IMDb

- Flashdance at the TCM Movie Database

- Flashdance at Box Office Mojo

- 1983 films

- 1980s dance films

- 1983 romantic drama films

- American dance films

- American romantic drama films

- 1980s English-language films

- Fictional portrayals of the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police

- Films about interclass romance

- Films adapted into plays

- Films directed by Adrian Lyne

- Films produced by Don Simpson

- Films produced by Jerry Bruckheimer

- Films scored by Giorgio Moroder

- Films set in Pittsburgh

- Films set in Pennsylvania

- Films shot in Pittsburgh

- Films that won the Best Original Song Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Joe Eszterhas

- Paramount Pictures films

- PolyGram Filmed Entertainment films

- Jerry Bruckheimer Films films

- Films about striptease

- Breakdancing films

- 1980s American films

- 1980s musical drama films

- English-language romantic drama films

- English-language musical drama films

- 1983 musical films