Belisario Betancur

Belisario Betancur | |

|---|---|

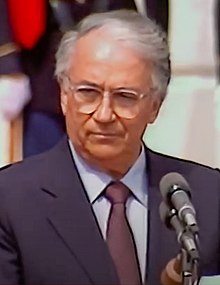

Betancur in 1985 | |

| 67th President of Colombia | |

| In office 7 August 1982 – 7 August 1986 | |

| Preceded by | Julio César Turbay Ayala |

| Succeeded by | Virgilio Barco Vargas |

| Ambassador of Colombia to Spain | |

| In office 16 December 1975 – January 1977 | |

| President | Alfonso López Michelsen |

| Preceded by | Álvaro Lloreda Caicedo |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Hoyos Arango |

| Minister of Labour | |

| In office 7 August 1962 – 23 April 1963 | |

| President | Guillermo León Valencia |

| Preceded by | Juan Benavides Patron |

| Succeeded by | Castor Jaramillo Arrubla |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Belisario Betancur Cuartas 4 February 1923 Amagá, Antioquia, Colombia |

| Died | 7 December 2018 (aged 95) Bogotá, D.C., Colombia |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouses | Dalita Rafaela Navarro Palmar

(m. 2000–2018) |

| Children | Three; including Diego |

| Alma mater | Pontifical Bolivarian University (JD) |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Belisario Betancur Cuartas (4 February 1923 – 7 December 2018) was a Colombian politician who served as the 67th President of Colombia from 1982 to 1986. He was a member of the Colombian Conservative Party. His presidency was noted for its attempted peace talks with several Colombian guerrilla groups. He was also one of the few presidents to abstain from participating in politics after leaving office.

Early life

[edit]Betancur was born in the Morro de la Paila district of the town of Amagá, Antioquia, in 1923.[1][2] His parents were Rosendo Betancur, a blue-collar worker, and Ana Otilia Cuartas, a businesswoman.[2] Betancur's mother died in 1950. He is of French descent.[3]

Betancur traveled to the city of Medellín, where he enrolled in the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana.[3] In 1955, Betancur graduated in jurisprudence and obtained a degree in law and economics.[3]

Political career

[edit]Betancur began his political career as a deputy in the Antioquia Departmental Assembly, where he served from 1945 to 1947.[4] He served as a Representative to the National Chamber for the departments of Cundinamarca and Antioquia, and was a member of the National Constituent Assembly from 1953 to 1957.[5]

Betancur was the Minister of Labor in 1963 and Ambassador to Spain from 1975 to 1977.[5]

He ran for president as an independent Conservative candidate in the election of 1970, coming in third.[6] He again ran as the official Conservative candidate in the election of 1978, but was defeated by Julio César Turbay Ayala.[6]

Presidency

[edit]Betancur was finally elected President in 1982 and served until 1986.[6] As President, he helped found the Contadora Group to bring about peace in Central America, began democratic reforms by incorporating the principal armed movements into civil life, promoted low-cost housing and open universities, began a literacy campaign and endorsed tax amnesty.[7]

During his term, the government approved the mayoral election law, municipal and departmental reforms, judicial and congressional reforms, the television statute, the national holiday law, and the new Código Contencioso Administrativo.[8][9] His administration began the exploration and export of coal in the Cerrejón North region and the broadcast of the regional television channels Teleantioquia and Telecaribe.[10]

| Colombia's four failed peace talks[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | President | Ended because |

| 1982–1985 | Belisario Betancur | Most Supreme Court Justices were killed when M-19 commandos and the Army fought for control of the building |

| 1986–1990 | Virgilio Barco Vargas | FARC ambush killed 26 soldiers in Caquetá |

| 1990–1992 | César Gaviria Trujillo | FARC attack on the Senate President. FARC kidnapping and killing of an ex-cabinet member. |

| 1998–2002 | Andrés Pastrana Arango | FARC kidnapping of Senator |

Betancur was also noted for his attempts to bring peace to his country.[12] During his administration he initiated peace talks with several Colombian guerrilla groups.[13] The controversial Palace of Justice siege occurred in late 1985, less than a year before the end of his presidential term.[14]

He was president during the 1985 eruption of Nevado del Ruiz, which killed over 20,000 people.[15]

Post-presidency

[edit]Betancur retired from politics after he left office in 1986.

Betancur was an Honorary Member of the Club of Rome for Latin America,[16] Chairman of the Truth Commission for El Salvador,[17] and President of the Santillana for Latin America Foundation in Bogotá.[5] He also was a founding member of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.[5]

Personal life

[edit]In 1946, Betancur married Rosa Helena Álvarez Yepes.[18] Together, they had three children including diplomat Diego Betancur Álvarez.[19] Álvarez Yepes died in 1998.[18] In October 2000, Betancur married Dalia Rafaela Navarro Palmar.[20]

Death

[edit]On 6 December 2018, Betancur was hospitalized in Bogotá in a critical condition, suffering from a kidney infection.[21][22] Vice President Marta Lucía Ramírez prematurely announced his death on Twitter, but later retracted her statement.[23][24] Betancur died the following day from the illness, aged 95.[25][26]

Before his death, Betancur said he did not wish to have a state funeral and expressed interest in being buried at Jardines del Recuerdo Cemetery in Bogotá.[27] On 8 December, his funeral was held with President Iván Duque Márquez and former presidents Juan Manuel Santos and César Gaviria in attendance.[28][29] He was buried at Jardines del Recuerdo Cemetery later that day following a mass at Gimnasio Moderno in Bogotá.[30][29]

Honours

[edit]Betancur was the recipient of honorary doctorates from the University of Colorado and Georgetown University.[31][32] He received the Prince of Asturias Peace Award of Spain in 1983.[33]

References

[edit]- ^ Sabsay, Fernando Leónidas (2006). Profile of Belisario Betancur Cuartas. p. 309. ISBN 9789500263955. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Belisario Betancur Cuartas (1982-1986)". Office of the President. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Arismendi Posada, Ignacio; Gobernantes Colombianos; trans. Colombian Pryhjtyjyhfnpfjesidents; Interprint Editors Ltd., Italgraf, Segunda Edición; Page 255; Bogotá, Colombia; 1983

- ^ "Biography of Belisario Betancur (1923-VVVV)". The Biography.us. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Belisario Betancur". Pass.va. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ a b c "Belisario Betancur Cuartas: President-elect of Colombia". UPI. 1 June 1982. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Colombia president begins reorganization". UPI. 2 August 1983. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Lessons of the Colombian Constitutional Reform of 1991" (PDF). Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Belisario Betancur Cuartas" (in Spanish). Colombia.com. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Television en Colombia" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Why did the Colombia Peace Process Fail?" (PDF). The Tabula Rasa Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2006. [PDF file]

- ^ "History of peace talks with Colombia's ELN guerrillas". Colombia Reports. 27 October 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Colombia's half-century of conflict that led to historic peace deal". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "33 years ago, rebels allegedly backed by Pablo Escobar stormed Colombia's Palace of Justice — here's how the terrifying siege went down". Business Insider. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Colombia Reports a Suspension of Rescue Efforts". The New York Times. 18 November 1985.

- ^ "Honorary Member | THE CLUB OF ROME (www.clubofrome.org)". www.clubofrome.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-29. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- ^ "Truth Commission: El Salvador". USIP. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ a b "MURIÓ ROSA HELENA ALVAREZ DE BETANCUR". El Tiempo. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "HIJO DE TIGRE SALE... ROJO". Semana. 27 June 1983. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "De Turbay, Belisario y otras movidas matrimoniales". El Espectador. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Un tuit de la vicepresidenta de Colombia da por muerto a Belisario Betancur" (in Spanish). El Pais. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Expresidente colombiano Belisario Betancur Cuartas continúa hospitalizado". El Colombian. 6 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Aclaración: desmienten rumor sobre la muerte de Belisario Betancur". El Colombia. 6 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Marta Lucía Ramírez on Twitter". Twitter. 6 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Confirmado: falleció el expresidente Belisario Betancur". RCN Radio. 7 December 2018. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "Belisario Betancur, 95, Colombia President During Rebel Siege, Dies". The New York Times. 8 December 2018.

- ^ "¿Por qué el funeral de Belisario Betancur no será uno de Estado?". Conexion Capital. 9 December 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "Personalidades de la política nacional se unen en acto fúnebre de Belisario Betancur". Asuntos Legales. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ a b "El último adiós al expresidente Belisario Betancur". El Espectador. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "Sepelio de Belisario Betancur será en el cementerio Jardines del Recuerdo". LAFM. 9 December 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees, University Medals and Distinguished Service Awards Full List A-Z". University of Colorado. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Belisario Betancur" (in Spanish). UPV. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "BELISARIO BETANCUR". FPA.es. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

External links

[edit]- 1923 births

- 2018 deaths

- Bettencourt family

- People from Antioquia Department

- Pontifical Bolivarian University alumni

- Colombian Conservative Party politicians

- Ambassadors of Colombia to Spain

- Presidents of Colombia

- Members of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences

- Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Colombian anti-communists