Neuropsychological assessment

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Neuropsychology |

|---|

|

Over the past three millennia, scholars have attempted to establish connections between localized brain damage and corresponding behavioral changes. A significant advancement in this area occurred between 1942 and 1948, when Soviet neuropsychologist Alexander Luria developed the first systematic neuropsychological assessment, comprising a battery of behavioral tasks designed to evaluate specific aspects of behavioral regulation. During and following the Second World War, Luria conducted extensive research with large cohorts of brain-injured Russian soldiers.

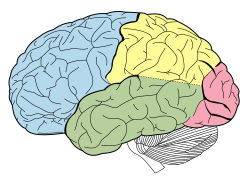

Among his most influential contributions was the identification of the critical role played by the frontal lobes of the cerebral cortex in neuroplasticity, behavioral initiation, planning, and organization. To assess these functions, Luria developed a range of tasks—such as the Go/no-go task, "count by 7," hands-clutching, clock-drawing task, repetitive pattern drawing, word associations, and category recall—which have since become standard elements in neuropsychological evaluations and mental status examinations.

Due to the breadth and originality of his methodological contributions, Luria is widely regarded as a foundational figure in the field of neuropsychological assessment. His neuropsychological test battery was later adapted in the United States as the Luria-Nebraska neuropsychological battery during the 1970s. Many of the tasks from this battery were subsequently incorporated into contemporary neuropsychological assessments, including the Mini–mental state examination (MMSE), which is commonly used for dementia screening.

History

[edit]Neuropsychological assessment has traditionally been employed to evaluate the degree of impairment in specific cognitive or functional abilities and to assist in identifying potential areas of brain damage resulting from brain injury or neurological illness. With the development of advanced neuroimaging techniques, the precise localization of space-occupying lesions can now be achieved with greater accuracy, thereby shifting the focus of neuropsychological assessment toward the evaluation of cognitive and behavioral functioning. This includes the systematic examination of the impact of brain injury or other neuropathological processes on an individual.

A central component of neuropsychological assessment involves the administration of standardized neuropsychological tests, which provide a structured means of evaluating cognitive abilities. However, neuropsychological assessment encompasses more than the mere administration and scoring of these tests and screening instruments. It is critical that such assessments also incorporate an evaluation of the individual's mental status, particularly in cases involving suspected Alzheimer's disease or other types of dementia.[1]

Cognitive domains typically assessed include orientation, memory and new learning, general intellectual functioning, language abilities, visuoperceptual skills, and executive function. Nevertheless, comprehensive clinical neuropsychological assessment extends beyond cognitive evaluation to consider psychological factors, personality characteristics, interpersonal relationships, and the broader contextual and environmental circumstances relevant to the individual.

Assessment may be carried out for a variety of reasons, such as:

- Clinical evaluation, to understand the pattern of cognitive strengths as well as any difficulties a person may have, and to aid decision making for use in a medical or rehabilitation environment.

- Scientific investigation, to examine a hypothesis about the structure and function of cognition to be tested, or to provide information that allows experimental testing to be seen in context of a wider cognitive profile.

- Medico-legal assessment, to be used in a court of law as evidence in a legal claim or criminal investigation.

Miller outlined three broad goals of neuropsychological assessment. Firstly, diagnosis, to determine the nature of the underlying problem. Secondly, to understand the nature of any brain injury or resulting cognitive problem (see neurocognitive deficit) and its impact on the individual, as a means of devising a rehabilitation programme or offering advice as to an individual's ability to carry out certain tasks (for example, fitness to drive, or returning to work). And lastly, assessments may be undertaken to measure change in functioning over time, such as to determine the consequences of a surgical procedure or the impact of a rehabilitation programme over time.[2]

Diagnosis of a neuropsychological disorder

[edit]Certain types of damage to the brain will cause behavioral and cognitive difficulties. Psychologists can start screening for these problems by using either one of the following techniques or all of these combined:

History taking

[edit]This includes gathering medical history of the patient and their family, presence or absence of developmental milestones, psychosocial history, and character, severity, and progress of any history of complaints. The psychologist can then gauge how to treat the patient and determine if there are any historical determinants for his or her behavior.

Interviewing

[edit]Psychologists use structured interviews in order to determine what kind of neurological problem the patient might be experiencing. There are a number of specific interviews, including the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, Neuropsychological Impairment Scale, Patient's Assessment of Own Functioning, and Structured Interview for the Diagnosis of Dementia.[3]

Test-taking

[edit]Scores on standardized tests of adequate predictive validity predictor well current and/or future problems. Standardized tests allow psychologists to compare a person's results with other people's because it has the same components and is given in the same way. It is therefore representative of the person's's behavior and cognition. The results of a standardized test are only part of the jigsaw. Further, multidisciplinary investigations (e.g. neuroimaging, neurological) are typically needed to officially diagnose a brain-injured patient.[4]

Intelligence testing

[edit]Testing one's intelligence can also give a clue to whether there is a problem in the brain-behavior connection. The Wechsler Scales are the tests most often used to determine level of intelligence. The variety of scales available, the nature of the tasks, as well as a wide gap in verbal and performance scores can give clues to whether there is a learning disability or damage to a certain area of the brain.[3]

Testing other areas

[edit]Other areas are also tested when a patient goes through neuropsychological assessment. These can include sensory perception, motor functions, attention, memory, auditory and visual processing, language, problem solving, planning, organization, speed of processing, and many others. Neuropsychological assessment can test many areas of cognitive and executive functioning to determine whether a patient's difficulty in function and behavior has a neuropsychological basis.[5]

Information gathered from assessment

[edit]Tsatsanis and Volkmar assert that neuropsychological assessment can yield valuable insights into the specific nature of a psychological or neurological disorder, thereby informing the development of an appropriate treatment plan.[4] Such assessments assist in clarifying the characteristics of the disorder and in evaluating the cognitive functioning associated with it. Furthermore, neuropsychological evaluations can help clinicians monitor the developmental trajectory of a disorder, enabling the prediction of potential future complications and the formulation of comprehensive treatment strategies.

Various forms of assessment may also be utilized to identify an individual's risk for developing specific conditions. However, a single assessment at one point in time may not provide sufficient information for long-term treatment planning, given the potential variability in behavioral and cognitive functioning. Consequently, repeated assessments are often necessary to determine whether the current treatment approach remains appropriate. Through neuropsychological testing, researchers can identify specific brain regions that may be impaired, based on observed cognitive and behavioral patterns.[4]

Benefits of assessment

[edit]Neuropsychological assessment serves as a valuable tool in providing an accurate diagnosis, particularly in cases where the clinical presentation is unclear. Such assessments enable psychologists to identify the specific disorder affecting the patient, thereby informing more targeted and effective treatment strategies. These evaluations also assist in determining the severity of cognitive or neurological deficits, facilitating informed decision-making for both clinicians and patients.[6] Additionally, neuropsychological assessments are useful in monitoring the progression of degenerative conditions through repeated evaluations over time.

These assessments also have important applications in the field of forensic psychology, particularly in cases where a defendant's mental competency is under scrutiny due to suspected brain injury or neurological impairment. In such contexts, neuropsychological testing may reveal cognitive deficits that are not detected through neuroimaging. Moreover, it can aid in the identification of malingering, wherein an individual may be feigning symptoms to obtain a reduced sentence.[7]

Typically, the administration of neuropsychological tests requires between 6 and 12 hours, depending on the scope and complexity of the evaluation. This timeframe does not include the additional tasks performed by the psychologist, such as scoring, interpretation of results, case formulation, and the preparation of a comprehensive written report.[7]

Qualifications for conducting assessments

[edit]Neuropsychological assessments are typically conducted by doctoral-level psychologists (Ph.D. or Psy.D.) who have received specialized training in neuropsychology. These professionals are referred to as clinical neuropsychologists. The qualifications, training requirements, and scope of practice for clinical neuropsychologists are defined by the widely recognized Houston Conference Guidelines.[8] These individuals typically complete postdoctoral training in areas such as neuropsychology, neuroanatomy, and brain function. The majority are licensed psychologists practicing within their respective jurisdictions.[4]

Advancements in the field have enabled certain tasks, such as the administration of specific neuropsychological instruments, to be performed by trained professionals known as psychometrists. However, the interpretation of test results and the formulation of clinical conclusions remain under the purview of the supervising clinical neuropsychologist.

See also

[edit]- Clinical neuropsychology – Sub-field of neuropsychology concerned with the applied science of brain-behaviour relationships

- List of neurological conditions and disorders

- Mini-SEA – Tests evaluating social and emotional cognition impairment

- Neurocognition – Cognitive functions related to a brain region

- Neuroimaging – Set of techniques to measure and visualize aspects of the nervous system

- Neuropsychology – Study of the brain related to specific psychological processes and behaviors

- Neuropsychological test – Assess neurological function associated with certain behaviors and brain damage

- Psychological testing – Administration of psychological tests, such as psychometrics

References

[edit]- ^ Gregory, Robert. "Psychological Testing, 5th ed.". Pearson, 2007, p.466.

- ^ Miller, E. (1992) Some basic principles of neuropsychological assessment. In J.R. Crawford, D.M. Parker, W.M. McKinlay (eds) A handbook of neuropsychological assessment. Hove: Laurence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-86377-274-9

- ^ a b "Neuropsychological Assessment". St. John's University. Archived from the original on 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ a b c d Tsatsanis & Volkmar. "Unraveling the Neuropsychological Assessment" (PDF). The Source. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-12-09. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ "Neuropsychological Assessment". New York Assessment. December 2015. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ "Neuropsychological and Psychoeducational Testing for Children and Adults". New York Assessment. December 2015. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Burke, Harold L. "Benefits of Neuropsychological Assessment". Archived from the original on 2012-01-03. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ^ "THE HOUSTON CONFERENCE ON SPECIALTY EDUCATION AND TRAINING IN CLINICAL NEUROPSYCHOLOGY" (PDF). American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology. September 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Baer, Lee; Blais, Mark A., eds. (3 October 2009). Handbook of Clinical Rating Scales and Assessment in Psychiatry and Mental Health. Springer. ISBN 978-1-58829-966-6. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- Davis, Andrew, ed. (2011). Handbook of Pediatric Neuropsychology. New York: Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8261-0629-2. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- David A. Baker (June 2012). "Handbook of Pediatric Neuropsychology". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology (Review). 27 (4): 470–471. doi:10.1093/arclin/acs037.

- Lezak, Muriel D.; Howieson, Diane B.; Bigler, Erin D.; Tranel, Daniel (2012). Neuropsychological Assessment (Fifth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539552-5. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- Peter J Anderson (April 2013). "Leader of the Pack". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (Review). 19 (4). doi:10.1017/S1355617713000337. S2CID 144213730.

- Loring, David W., ed. (1999). INS Dictionary of Neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506978-5. This standard reference book includes entries by Kimford J. Meador, Ida Sue Baron, Steven J. Loring, Kerry deS. Hamsher, Nils R. Varney, Gregory P. Lee, Esther Strauss, and Tessa Hart.

- Miller, Daniel C. (3 January 2013). Essentials of School Neuropsychological Assessment (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-17584-2. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- Reddy, Linda A.; Weissman, Adam S.; Hale, James B., eds. (2013). Neuropsychological Assessment and Intervention for Youth: An Evidence Based Approach to Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-4338-1266-8. OCLC 810409783. Retrieved 15 June 2014. This collection of articles for practitioners includes chapters by Linda A. Reddy, Adam S. Weissman, James B. Hale, Allison Waters, Lara J. Farrell, Elizabeth Schilpzand, Susanna W. Chang, Joseph O'Neill, David Rosenberg, Steven G. Feifer, Gurmal Rattan, Patricia D. Walshaw, Carrie E. Bearden, Carmen Lukie, Andrea N. Schneider, Richard Gallagher, Jennifer L. Rosenblatt, Jean Séguin, Mathieu Pilon, Matthew W. Specht, Susanna W. Chang, Kathleen Armstrong, Jason Hangauer, Heather Agazzi, Justin J. Boseck, Elizabeth L. Roberds, Andrew S. Davis, Joanna Thome, Tina Drossos, Scott J. Hunter, Erin L. Steck-Silvestri, LeAdelle Phelps, William S. MacAllister, Jonelle Ensign, Emilie Crevier-Quintin, Leonard F. Koziol, and Deborah E. Budding.

- Riccio, Cynthia A.; Sullivan, Jeremy R.; Cohen, Morris J. (28 January 2010). Neuropsychological Assessment and Intervention for Childhood and Adolescent Disorders. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118269954. ISBN 978-0-470-18413-4.

- Strauss, Esther; Sherman, Elizabeth M.; Spreen, Otfried (2006). A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515957-8. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Sherman, Elizabeth M.; Brooks, Brian L., eds. (2012). Pediatric Forensic Neuropsychology (Third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973456-6. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Leah Ellenberg (August 2013). "Pediatric Forensic Neuropsychology". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology (Review). 28 (5): 510–511. doi:10.1093/arclin/act033.

- Whishaw, Ian Q.; Kolb, Bryan (1 July 2009). Fundamentals of human neuropsychology (Sixth ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7167-9586-5. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- Gina A. Mollet (Spring 2008). "TEXTBOOK REVIEW: Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology, 6th Edition" (PDF). The Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education. 6 (2): R3 – R4.

External links

[edit]- UNC School of Medicine Department of Neurology (24 February 2011). "Neuropsychological Evaluation FAQ". University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Retrieved 17 June 2014.