Jules Bonnot

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Portuguese. (August 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

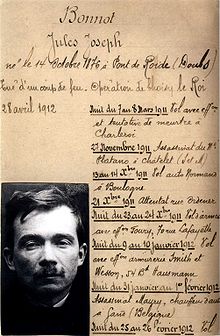

Jules Joseph Bonnot (14 October 1876 – 28 April 1912) was a French soldier, anarchist, bank robber, and murderer. He is notorious for his role in the French anarchist band "The Bonnot Gang" that committed many crimes in early 20th-century Paris.

Born in Pont-de-Roide, Bonnot experienced many hardships in his youth, such as his mother dying when he was a child. Before his gang affiliation and time serving in the army, he had several run-ins with the law as a teenager. In 1887, he joined the French army as a mechanic, which resulted in an expertise in motor vehicles. After leaving the army, Bonnot adopted anarchist ideas in response to his frustration with the bourgeois society and followed a philosophy called illegalism.

Soon after, Bonnot formed the notorious "Bonnot Gang" in Paris, France with several fellow anarchists. They specialized in bank robberies utilizing motor vehicles to escape. From 1911 to 1912, the gang went on to commit many crimes around France that resulted in the deaths of many, including Bonnot's.

Early life

[edit]

Jules Bonnot was born on 14 October 1876 in Pont-de-Roide, France, a small commune in eastern France. His father labored as a smelter at a factory close to his childhood home. His father also struggled with alcoholism. When he was five years old, his mother died, leaving his grandmother to raise him throughout his entire childhood. In school, Bonnot was very intelligent; however, he lacked work ethic and was described as "lazy" and "insolent" by one of his teachers. When Bonnot reached his adolescence, his father remarried. Bonnot's early life took a turn for the worse when his brother Justin drowned himself in the waters of a nearby river due to heartbreak.[1] As he got older, Bonnot developed a short temper and got in several fights at a local bar when he would go out into town. He even spent several days in prison after severely beating another person. Like his father, he also worked in a local factory but was promptly let go after robbing from the worksite, so he left for the town of Nancy, France in search of employment. When he was residing there, he was placed in jail for a period of three months after striking a members of the local police. As a result, Bonnot's father ceased all communication with him for he had disappointed him.[2]

At the age of twenty-one, Bonnot was conscripted into the French army for a mandatory three years. He served in the 133rd Line regiment that was stationed near Lyon, France. During his time serving, Bonnot behaved himself and gained experience with the intricacies of the motor vehicles within the unit. When he finished his three years, he became engaged to a seamstress from Vouvray, France in 1900, named Sophie-Louise Burdet. They were married in August 1901, and they left to Bellegrade, France where Bonnot was employed at another factory. As a theme that was common in Bonnot's life, more tragic events unfolded. Bonnot's wife, Sophie, gave birth to a daughter in 1902 that only lived for four days. At the same time, Bonnot bounced around three different jobs but was fired for being violent and unruly towards his superiors. In 1903, Sophie gave birth to a son, who they named Justin after Bonnot's late brother. Later in 1903, when Bonnot contracted a case of tuberculosis, his wife Sophie left him to live in Dijon, France with a lover. Despite his calls for the custody of their son, Sophie refused every attempt and ceased all communication.[2]

Adoption of Illegalism

[edit]

In 1907, Bonnot began working at a factory as a mechanic in Lyon. As a result, he acquired a driver's license. Bonnot became frustrated with the constant unemployment and poverty. He felt that the new French society had turned its back on the common man, the worker, and the proletariat.[2] During this time, he joined the local anarchist and individualist meetings and partook in counterfeiting, which he learned from several members of the group. The group was made up of like-minded individuals frustrated with the bourgeois and capitalistic society.[1]

With another member of the anarchist group named Platano, Bonnot began burglarizing local companies and houses with the usage of his driver's license. According to Bonnot, the best way to fight against this new French society was to live outside the law and to get retribution against the wealthy. He began specializing in using motor vehicles to make a quick getaway from each incident. His group of anarchists burglarized many items that they rented a place out to store it all. In one particular occasion, Bonnot stole upwards of thirty-five thousand francs by utilizing the motor vehicle to great effect. He always considered himself as a professional burglar and favored wealthy outfits, a well-groomed appearance, and swift robberies.[2]

This philosophy that he and his anarchist partners adopted and lived by was illegalism, a form of anarchism. In late 1911, the garages that held all the robbed items were discovered by the police. In response, both Bonnot and Platano fled to Paris; however, in a freak accident, Platano was fatally shot while fiddling around with his own pistol. As a result, blame was inevitably placed on Bonnot, for Platano had a considerable amount of money under his name. Bonnot then became wanted for murder and burglary by the Lyon police.[1]

The Bonnot Gang

[edit]

Upon returning to Paris, Bonnot lacked money as most of the stolen items remained in Lyon. Bonnot felt he had no other choice but to continue his life of crime because of his standing in society and the warrants for his arrest. Thus, he joined a group of anarchists that were known to write issues of L'Anarchie.[3] Together with other local anarchists, they formed "The Bonnot Gang," an act of rebellion against their society. The group consisted of Edouard Carouy, André Soudy, Stephen Monier, René Valet, Raymond Callemin, Octave Garnier, and others, all whom were local anarchists of French and Belgian descent.[3] Their common denominator was their hatred of bourgeois society and the warrants for their incarceration.[4]

When Bonnot's frustration with capitalistic society grew to a breaking point, he decided that bank robberies were the most suitable expression of the sentiments of the Illegalists. The Bonnot Gang began by robbing a rare luxury car, a Delaunay-Belleville, to serve as the getaway vehicle for their crimes.[1] This theft, in particular, was a triumph for Bonnot because it proved to him that the bourgeois were vulnerable to their exploits. The gang then built up an arsenal of weapons and a collection of hiding spots from the police.[2] In late December 1911, the gang robbed and shot a bank messenger, stealing five thousand francs and bonds worth upwards of one hundred thousand francs. With this crime, several newspapers put up notices of a reward for the capture of the members of "The Bonnot Gang," and they were notorious among the general public of Paris as car bandits, an unprecedented new form of crime as motor vehicles had not been fully integrated into society at that point. This crime became known as one of the first robberies utilizing a motor vehicle to leave the crime scene.[1] In light of their attacks against the capitalist society, the gang was able to garner support from some of the general public that sympathized with their hatred of the bourgeois. Bonnot never considered himself as the leader of the gang because each member played a crucial role in each crime; however, because of his past notoriety and skills with motor vehicles, Bonnot was stamped as the face of the group.[2]

1912 crime spree and Bonnot's death

[edit]

Once the year turned 1912, "The Bonnot Gang" were beginning their infamous series of crimes. In addition to France, the gang commenced expanding their crime to Belgium. In January, the gang murdered two elderly people in their houses and stole several thousands of francs.[2] In Paris, they successfully sold stolen goods for eight thousand francs and robbed a wealthy residence. Later that month, several friends of the members of the gang were arrested and interrogated by the French police. Bonnot and Octave Garnier were able to evade capture while they were in Lyon.[3]

After taking a train to Paris and then traveling to Ghent, Garnier and Bonnot murdered a chauffeur and severely wounded a watchman as they attempted to steal two cars but returned to Paris emptyhanded in late January. While there, several members altered their appearance in order to evade arrest.[5] Instead of laying low, Bonnot Bonnot and Garnier continued their bouts of crime, venturing into Belgium and southern France at times.[2]

In late February, the duo traveled to a wealthy neighborhood of Paris and robbed another Delaunay-Belleville and changed the plates. While on their way to Southern France, the car broke down and was repaired. Bonnot, in a hurry after the delay, sped at significant speed and nearly caused an accident in a suburb of Paris. A police officer spotted their traffic infraction and attempted to stop the vehicle only to be mortally wounded. With Bonnot at the wheel, the gang's vehicle ran over and severely injured a young woman while in a haste to leave the scene. With the murder of the policeman, the French ramped up their efforts to round up the "bandits" and the general public was placed on high alert to report any suspicious activity directly to the French authorities.[2]

In late March, the group attempted to rob vehicles owned by the bourgeois in two different instances and came up empty-handed in both. As a result, they plotted to rob a car in broad daylight in the middle of a Parisian road. On 25 March, they targeted a newly purchased luxury limousine that was being delivered. When the limousine was most vulnerable in a suburb of Paris, Bonnot and Garnier shot the passengers and hijacked the vehicle. Immediately, the gang embarked towards a bank that was seventy kilometers away from the scene. They entered, shot three bank clerks, and got away from the French police with fifty thousand francs and without any confrontation.[2]

After this event, French police were placed on high alert and armed with revolvers in order to capture the gang once and for all. The infamy of the Bonnot Gang and the driving prowess of Bonnot was instilling fear in all of the French citizens.[1] In the following days, some of the members of the Bonnot Gang were captured by the French police, and on April 24, while in hiding, Bonnot was surprised by police. He quickly drew his weapon and killed a policeman, wounded another, and evaded capture; however, four days later, the police caught him hiding in a residence in Choisy-le-Roi.[1] Bonnot bunkered himself in the house while under siege by upwards of five hundred police men. He was able to wound three officers and fend off the force before the front of the residence was blown up with dynamite. Bonnot was shot ten times before finally being captured. The following day, April 28, 1912, Bonnot succumbed to his injuries and died in his hospital bed. He was not the only member of the gang to be killed. Rene Valet and Octave Garnier were killed the next month by French police in a shootout.[3]

Legacy

[edit]After his death, the gang's and Bonnot's notoriety was immortalized in French history forever. His expertise in automobile theft and the usage of these vehicles to facilitate an escape from a crime were a precedent for future crimes.[1] The remaining members of the gang was tried for their crimes and many of them were executed as a result of their actions. In the days after Bonnot's death, many anarchists in Paris attempted their own robberies on bourgeois vehicles and proclaimed their Illegalist views in support of the gang. These acts of crime were met with a swift response from the Paris police in order to discourage any more criminals from recreating the gang's crime spree. Any proletariat that stated their support for Bonnot were jailed instantly to discourage any rebellion against the upper class. Bonnot was either seen as a martyr for the fight against the bourgeois or a tyrant that was a threat to the stability of society. The French bourgeois made many efforts to shun any attempt to tear down the upper class.[2]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Merriman, John M. (2017). Ballad of the anarchist bandits: the crime spree that gripped Belle Époque Paris (First ed.). New York: Nation Books. ISBN 978-1-56858-988-6. OCLC 1004671291.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Parry, Richard (1987). The Bonnot gang. Paul Avrich Collection (Library of Congress). London: Rebel Press. ISBN 978-0-946061-04-4.

- ^ a b c d Loadenthal, Michael (2017). The politics of attack: communiqués and insurrectionary violence. Contemporary anarchist studies. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-5261-1446-4.

- ^ Meltzer, Albert (1966), The Truth about the Bonnot Gang

- ^ Jensen, Richard Bach (2014). The battle against anarchist terrorism: an international history, 1878-1934. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03405-1.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jensen, Richard Bach (2014). The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878-1934. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03405-1. p. 350-351.

- Loadenthal, Michael (2017). The Politics of Attack: Communiqués and Insurrectionary Violence. Contemporary anarchist studies. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-5261-1446-4

- Meltzer, Albert (1966). "The Truth about the Bonnot Gang". The Anarchist Library.

- Merriman, John M. (2017). Ballad of the Anarchist Bandits: The Crime Spree that Gripped Belle Époque Paris (First edition ed.). New York: Nation Books. ISBN 978-1-56858-988-6

- "Paris "Auto Bandits" and their Crimes: Bonnot-Garnier Gang Broken Up After Long Chase and Spectacular Battle With Police and Soldier". The St. Louis Post Dispatch. 12 May 1912. p. 1.

- Parry, Richard (1987). The Bonnot Gang. London: Rebel Press. ISBN 978-0-946061-04-4

- Special Cable to The New York Times. "Bonnot Will Defied Society An Extraordinary Document Found on the Body of Paris Bandit Chief". 29 April 1912 The New York Times, p. 1

Further reading

[edit]- Cacucci, Pino. (2006) Without a Glimmer of Remorse. ChristieBooks. ISBN 1-873976-28-3.

- Parry, Richard. (1987) The Bonnot Gang. Rebel Press. ISBN 0-946061-04-1.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Jules Bonnot at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jules Bonnot at Wikimedia Commons